> Hello World // March 1, 2025

Hey, I'm Nizar—sharing my thoughts here. I'm a programmer who's always wanted to create a very simple red-and-black website, and this blog is my excuse to create it. You can drop me a line at

nizar@deriva.ai.

> How to Do a Code Review in the Era of Cursor and Claude Code // December 06, 2025

A while back, my friend gave me a piece of advice about code reviews that I still think about.

In the first weeks, he said, be a dictator.

Don’t tolerate anything—not even the things you’d normally let slide.

Set the bar painfully high.

Then, once the team internalizes the standard, switch back to being a nice human.I loved this mindset for a long time… until the ground shifted under our feet.Because today, with tools like Cursor, Claude Code, and every AI pair-programmer under the sun, the entire dynamic of writing and reviewing code is changing. On one hand, these tools are magical.

A single engineer suddenly feels like a team of five. On the other hand… the architecture quality can quietly erode. (That’s a post for another time..) But one thing hasn’t changed: Code review is still one of the last safety rails we have.The problem? We’re now getting PRs the size of small novels (:

Thousands of lines !!

Entire mini-systems in one shot !!

How the hell are you supposed to review that?

Over the past few months I explored a few approaches:

Approach 1: Ask engineers not to vibe-code.

Come on. We’re not dinosaurs (: Do you really believe I would do such a harm to my company?

Approach 2: Force tiny PRs.

Even if you break the work into tiny tasks, AI generates them so quickly that the reviewer still ends up facing the same total volume of code.Sounds nice, but AI accelerates output so much that even “tiny” tasks become massive PRs.

Accept reality and learn to review long PRs differently.

This is where things get interesting.Back when I studied accounting (yes, really), we had the exact same problem. Due diligence, audits, financial reviews… mountains of documents. Nobody reads everything.

Instead, you identify high-risk zones, dive deep where it matters, and sample the rest.

It’s probabilistic, not deterministic. And it works (most of the time). That’s basically how I do PR reviews today in the age of vibe-coding:

1. Start with the flow: Before looking at a single line of code, I ask engineers to draw the flow. A diagram, a short video walkthrough, anything. Then I trace it with them in the code.

If the flow makes sense, the code usually follows.

2. Map the high-risk areas: Authorization. External calls that cost money. Performance bottlenecks. Critical business logic.

These parts get my full attention—manual, old-school review.

3. Outsource the low-level nits to an LLM:

Formatting, refactors, “use switch not if,” naming issues. I let an agent handle all of that.

Humans focus on architecture; machines focus on tidiness.

The bigger shift: I think there’s a tradeoff emerging between speed and complete visibility.

CTOs are becoming visionaries.

Team leads are becoming architects.

Software engineers: They’re becoming leaders of small agent teams, where the AI does the typing and they do the thinking. Just like a CTO doesn’t know every line of code in the system, engineers won’t know every line either. But they’ll know the architecture, the abstractions, the interfaces—the parts that actually matter.Everything is moving fast.

Six months from now I’ll probably look back at this post and laugh, because someone will have invented a whole new framework for AI-era code reviews, and I’ll wonder:

How did I not think of that? But for now, this approach keeps me sane. And maybe it’ll help someone else survive a 4,000-line PR too.

> How AI is changing the way we build products — lessons from Deriva // August 10, 2025

I’ve been building products for over 20 years — basically since I was a kid. And I can tell you: AI isn’t just “another tool.” It’s rewriting the rules.Here are three things I’m learning as we go:

1. User journeys aren’t deterministic anymore

For most of my career, UX was about a fixed set of buttons, inputs and flows. You’d design paths to capture intent quickly and make the journey as smooth as possible.

Now? Users can just say what they want, like they’re talking to a friend, and expect the system to figure it out.

We’re moving from designing user experiences to building systems that can capture intent — which means UX engineers need to think less about screens and R&D engineers should think more about training models or orchestrating multi-agent systems that know how to capture intent.

2. Solutions that used to be impossible are suddenly possible

In past companies, the “solution space” was well defined. You knew what could be done and what couldn’t. With AI, the boundaries have shifted — and keep shifting.

The challenge now is to think bigger during customer interviews: spot the pain, but also imagine later on solutions that would have been impossible before.

3. Every new solution creates new problems

When AI makes something possible that wasn’t before, it almost always opens a new set of challenges.

For example: new ways to use AI often create entirely new attack vectors for cybersecurity teams to defend against.

In our work in DNA analysis and biology, the same thing happens — every time a capability appears (for example, think alphafold), it spawns fresh problems to solve.

That’s why in every customer interview I ask myself:

- What’s changing?

- What’s newly possible?

- And what brand-new problems will those changes create?

AI isn’t just changing how we build — it’s changing what’s possible, and even what problems we should be solving next.

> Reflecting on Abstractions, Vibe Coding, and Why People Defend the Old Ways // August 8, 2025

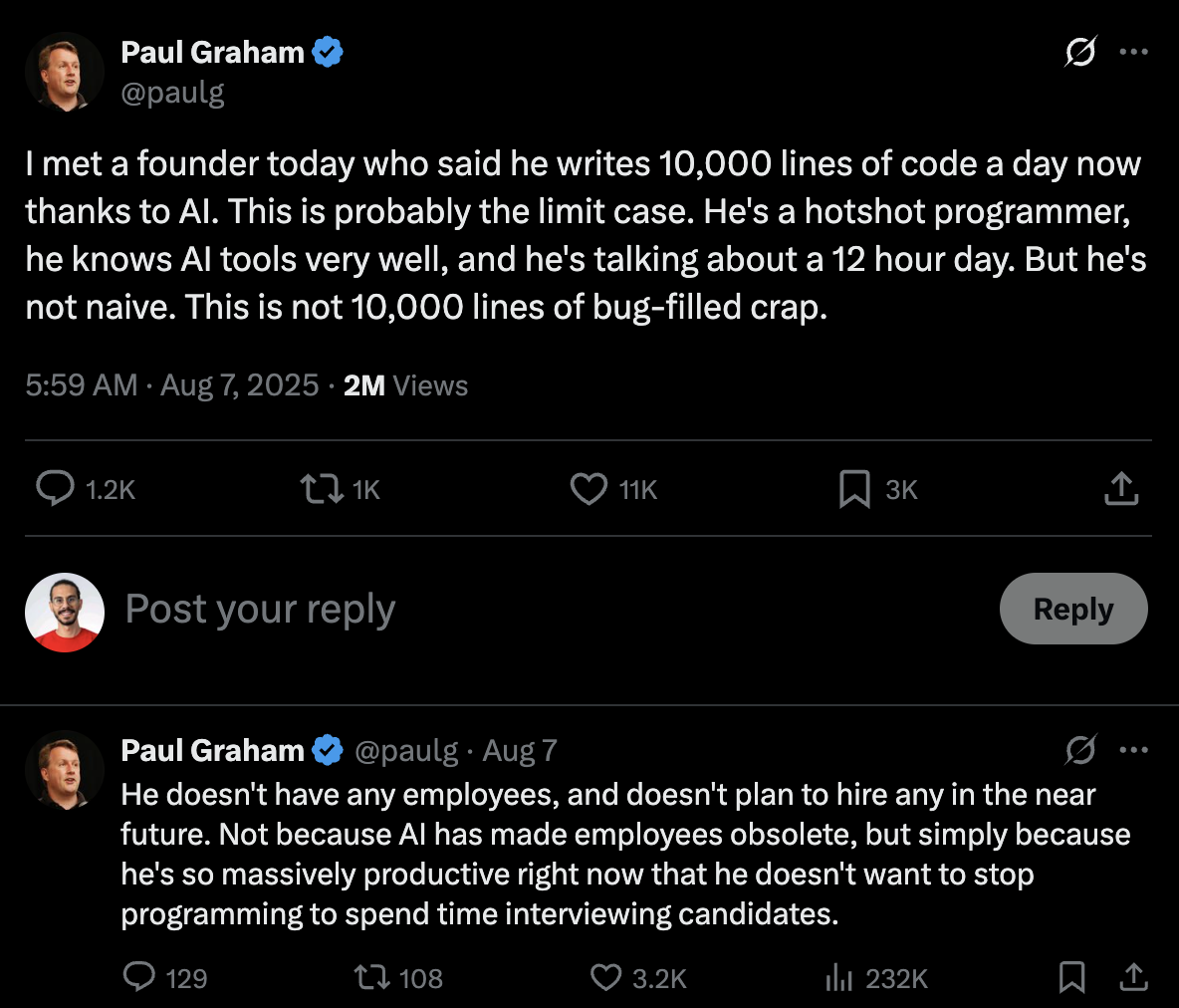

I’ve been thinking a lot about abstractions lately — and why people fight them.This started after reading something Paul Graham wrote the other day.

The replies? Full of people tearing it down — especially programmers (that I assume they are) with prestigious degrees. Which got me thinking.

Whenever you have something to lose, you defend it — even if it’s illogical.

History repeats this pattern:

- The bourgeoisie resisted expanding human rights because it symbolized change.

- Trained musicians mocked synthesized instruments.

- Developers with fancy degrees avoided using proven GitHub repos, preferring to reinvent the wheel (badly).

People who’ve invested years into mastering one way of doing things often push back the hardest when something easier comes along.

I think that one of my biggest advantages in companies was that I had no formal “system” to protect. I learned by trial and error, reading, experimenting, asking dumb questions. That made me comfortable trying new tech. It’s probably why I’m an entrepreneur today instead of a senior dev at some enterprise, pulling in a steady salary but never questioning the system.

I hate the name 'vibe coding'. But I love the concept. When I studied economics, the first lesson was about trade-offs: if you want something, you give up something. In music, I never liked DJing at first. I spent hours learning harmony and bass techniques, working with friends, tweaking every detail of sound.

Then someone would show up with Ableton Live and some DSP plugins and make something magical in minutes. At first it annoyed me. Then I realized: this is the same fear people have with new coding abstractions. I wasn’t the luthier who built my bass guitar. The luthier wasn’t the one who cut the tree. We all stand on layers of work we didn’t do. In the end, I chose to focus on music, not carpentry — because time is limited.

Low-level languages are “better” in the hands of an expert — but higher-level languages took over because speed mattered more than control. We traded perfection for iteration. That’s also how we moved from waterfall to agile. Now vibe coding is the next layer. Above languages. Above frameworks. It’s just faster. And yes, there will be bugs. But slowness is often more dangerous than bugs.So next time you’re tempted to criticize a higher-level abstraction, remember:

Someone once criticized the layer you’re standing on, too.

Oh, and in case you’re wondering — this post itself is an abstraction. I wrote it, but then AI gave it a polish. Layers on layers.

> Rethinking what engineering means to a company // Au2

At Deriva, we’re building with a mindset that wasn’t possible just a few years ago.

Take Maor Shlomo from Base44 — using next-gen coding tools, he built what used to require an entire engineering and marketing teams. These kinds of businesses are incredible, and they have changed how I think about what engineering should do inside a company.

I come from a product-led growth mindset, where everything in the company is in service of the product — and a great product markets itself. But supporting the product doesn’t just mean writing code. It means helping with go-to-market, hiring, business model, roadmap — the full lifecycle of the product.

Historically, engineering was too expensive to "waste" on anything but core product. But now? Engineering has become more accessible, faster, and way more powerful.

One great engineer can build, ship, and automate across multiple functions — all in parallel. So at Deriva, we don’t think of engineers as “just building features.” They build the holistic product/business.

They write agents that optimize conference attending. They filter recruiters and candidates (see my Chrome extension in previous post). They manage financials (see that post too). They support the product by supporting everything around it.The philosophy is simple: small teams, high leverage, zero silos. Everyone builds. Everyone automates. And the product leads the way.

> Cash‑Flow for Engineer‑Founders: The Stuff No One Taught You // July 30, 2025

Building a startup feels like a never‑ending boss fight: you clear one level (hiring) and—boom—a fresh one (closing deals, nailing GTM) spawns instantly. Meanwhile, a swarm of tiny but vital money tasks buzzes in the background, begging for attention.Below are the cash‑flow habits that keep me sane, borrowed from ex‑CFO friends and my own past life as an accountant. Steal what helps, ignore what doesn’t, and get back to shipping.

Know your numbers

Your bank balance is your Lean Startup handbook (I’m atheist—books beat Bibles!). Glance at it every day—or at least a few times a week. Runway and burn should flow off your tongue like a killer chorus.

Batch the boring stuff

Pay suppliers on just two preset days each month. Leave their requests pending in your bank portal and clear them all at once. You’ll slash context‑switching and make tracking spend a breeze.

Default to policy

Policies sound corporate, but here’s the trick: anytime a question stalls you—parking reimbursements, supplier terms—decide once, label it “policy,” and move on. Future you will thank past you.

Demand a monthly snapshot

Ask your bookkeepers for a trial balance every month or two. They work smarter, you see the full picture sooner.

Park idle cash in deposits

Hundreds of thousands—or millions—sitting idle? Toss it into short‑term deposits and earn interest while you sleep.

Tame service‑provider creep

Negotiate retention‑based fees instead of open‑ended hourly bills. Uncertainty is a beast; cage it early.

Split your currencies

Investors think in USD, your team gets paid in ₪. Track each separately to cut FX noise, then convert for board decks. Clearer visibility, fewer surprises.

Let code do the counting

Spreadsheets make me twitch. So I built a mini cash‑flow app that snapshots runway, tracks the cap table, pings me when something’s off. If you’re an early‑stage founder and hate Excel as much as I do, ping me—I’ll share access.

%20(1).png)

.png)

I’m lazy. Always have been. But here’s the thing: lazy engineers build the best tools. We find shortcuts. We automate. We vibe-code our way out of repetitive work.

If you want to use the tool ping me at nizar@deriva.ai or in linkedin and I'll share it.

> Cash‑Flow for Engineer‑Founders: The Stuff No One Taught You // July 30, 2025

Building a startup feels like a never‑ending boss fight: you clear one level (hiring) and—boom—a fresh one (closing deals, nailing GTM) spawns instantly. Meanwhile, a swarm of tiny but vital money tasks buzzes in the background, begging for attention.Below are the cash‑flow habits that keep me sane, borrowed from ex‑CFO friends and my own past life as an accountant. Steal what helps, ignore what doesn’t, and get back to shipping.

Know your numbers

Your bank balance is your Lean Startup handbook (I’m atheist—books beat Bibles!). Glance at it every day—or at least a few times a week. Runway and burn should flow off your tongue like a killer chorus.

Batch the boring stuff

Pay suppliers on just two preset days each month. Leave their requests pending in your bank portal and clear them all at once. You’ll slash context‑switching and make tracking spend a breeze.

Default to policy

Policies sound corporate, but here’s the trick: anytime a question stalls you—parking reimbursements, supplier terms—decide once, label it “policy,” and move on. Future you will thank past you.

Demand a monthly snapshot

Ask your bookkeepers for a trial balance every month or two. They work smarter, you see the full picture sooner.

Park idle cash in deposits

Hundreds of thousands—or millions—sitting idle? Toss it into short‑term deposits and earn interest while you sleep.

Tame service‑provider creep

Negotiate retention‑based fees instead of open‑ended hourly bills. Uncertainty is a beast; cage it early.

Split your currencies

Investors think in USD, your team gets paid in ₪. Track each separately to cut FX noise, then convert for board decks. Clearer visibility, fewer surprises.

Let code do the counting

Spreadsheets make me twitch. So I built a mini cash‑flow app that snapshots runway, tracks the cap table, pings me when something’s off. If you’re an early‑stage founder and hate Excel as much as I do, ping me—I’ll share access.

%20(1).png)

.png)

I’m lazy. Always have been. But here’s the thing: lazy engineers build the best tools. We find shortcuts. We automate. We vibe-code our way out of repetitive work.

If you want to use the tool ping me at nizar@deriva.ai or in linkedin and I'll share it.

> How I Hired a Team of Builders (and What I Learned) // July 24, 2025

Over the past few months, I set out to hire a small team of engineers—people I’d genuinely enjoy building with. Not just “good coders,” but real builders. People who love moving fast, figuring things out, and fighting through ambiguity. People who would thrive in a “quick and dirty, then polish” kind of world. Here’s what I looked for (and how it actually played out).

What I was looking for

- People I’d enjoy building with

- Quick-and-dirty mindset, then iterate

- Deep curiosity for tech

- Fast learners

- Fiercely independent

- Builder energy

- Fighter spirit

The hiring funnel (aka what I tried, what worked, what didn’t)

1. Filtering the noise: I posted the job on LinkedIn. Got flooded. Thousands of CVs. So I did what any good nerd would do: I built a bot. It scraped profiles, downloaded resumes, and ran them through an AI pipeline I hacked together using preset criteria.That got me down to ~5–10 promising candidates per day. Manageable.

I’m lazy. Always have been. But here’s the thing: lazy engineers build the best tools. We find shortcuts. We automate. We vibe-code our way out of repetitive work. This little tool scraped LinkedIn, filtered resumes, and ran them through an AI pipeline—so I could focus on talking to the best people, not drowning in CVs. Lazy + nerd = superpower.

If you want to use the tool ping me at nizar@deriva.ai or in linkedin and I'll share it.

2. Reaching out: Every day I blocked off an hour. Scanned the most interesting profiles. Sent out friendly WhatsApp intros: who I am, what we’re building, and a casual “want to chat?” - People who only reply during 9–5 hours? Filtered. People who take too long to reply? Filtered. People who reply with excitement? Gold.

3. Phone calls: I did 3–5 calls a day. I asked myself: Would I enjoy working with this person?Are they excited about tech? Are they a 9–5 employee or a true builder? Are they advanced? The vibe mattered just as much as the answers.

4. The assignment: This one was intentional.I created a multi-part assignment, each chapter using different tech stacks—some they likely never touched. It was ambitious on purpose. I wanted to see: Can they learn fast? Can they work independently? Do they enjoy the building process? Many ghosted. Some played it safe and stayed in their comfort zone. Others leaned hard on AI but clearly didn’t understand the code. A few stood out—they read the docs, did the work, and deeply understood what they shipped.

5. Follow-up meetings: I met with everyone who submitted, even if I knew we weren’t sure we're moving forward. Out of respect for their time. We talked code. We talked life. For the ones who seemed promising, I reached out to a past manager or team lead for a reference call.

6. The references: You’d be surprised how much you can learn from one question: “What could be better about [candidate]?” - That’s where the truth spills out. People don’t like to lie—but they will soften the truth if you ask the wrong question. Ask the right one, and you'll hear the real stuff.Many candidates didn’t make it past this step.

But in the end.. I went with my gut. I picked the people I felt the most excited to build with. The ones who had the energy, the curiosity, the hunger. And yeah—I made sure to reply to every single candidate who reached a call or an assignment, with honesty and humility.

On creating an edge as a startup

Let’s be real: we can’t outpay Google.So I asked myself: Why did I join startups when I had big company offers?

Because:

- I wanted to build, not be a cog.

- I loved trying new tech.

- I wanted to learn how startups work.

- I got fired up by a bold vision.

So I leaned into that in our job posts—talked about impact, helping people, real-life change, and yes, the wild tech we’re using.

And here’s something else: Good engineers often don’t optimize for salary. They optimize for meaning. For self-expression. For building something real.

A small A/B test that worked

I had a hunch: many great Arab programmers eventually settle in Haifa/North. They get tired of commuting to Tel Aviv. The daily traffic kills them.

So I ran an A/B test:

- Job post for Tel Aviv

- Job post for Haifa

The Tel Aviv post got more hits.

But Haifa? The quality was amazing.

I ended up hiring builders with 10+ years of experience, people who worked in legendary companies and could own a product end-to-end. All while being closer to home. All while bringing that big company knowledge to our tiny team.

What we have now

A team of real builders: They’re not just engineers—they’re superbuilders. End-to-end ownership, no hand-holding, and a ridiculous ability to turn ideas into real, working software.

What's next?

We’re building a company I’d want to work at if I were an employee. That means: friendships, shared experiences, and joy at work. So I’m planning a retreat. Not a PowerPoint retreat. A real one: Group bonding (shoutout to my scouts days), Laughter, Learning from each other:

A place where people want to come to work.

Not a place they count hours until they can leave.

And I’m pumped to tell you how it goes.

Stay tuned ✌️

> Not a Manual, Just My Journey: Notes on Customer Conversations // March 11, 2025

I believe that customer validation is a skill. There are two stages of validation: problem validation—determining whether the assumed problem truly exists—and problem-solution fit validation—confirming that the solution you propose is the optimal one.Product-wise, the most important hypothesis you’ll ever make during your startup journey is the problem hypothesis. If it’s wrong, it will be very hard to change later on, and the signals become more vague as you start to focus on other aspects of the product.I also believe that we learn different skills throughout life, and the best way to master them is through practice. Theory is great, but nothing can replace practice. I am a musician, and I’ve learned the hard way that knowing all the theory is useless if you don’t pick up your bass and practice; you’ll never truly play well. The same applies to programming. No matter how many design patterns you know, if you never encounter them in real-life programming, you will never internalize them. Now, I’m trying to apply the same methods I use in music and programming to my entrepreneurial journey.

Learning to Listen by Practicing

One of the main skills you need as an entrepreneur is the ability to conduct customer discovery calls. As simple as it might seem, these calls are very challenging, and it takes tens of calls to grasp how to do it effectively. The goal of these calls is to observe and listen carefully. This is especially challenging for a hyperactive person like myself because when a hypothesis turns out to be true, I get so excited that I want to share that excitement with the customer—to tell them, “This is what we found!” However, talking at this stage can cut short the customer’s chain of thought, and you risk losing the real data that comes when the customer validates your problem hypothesis and starts to elaborate. Learning to listen is a skill that must be developed; I don’t think people are born with it. I’ve worked with many talented product managers and it’s clear that the more interviews they conduct, the better they become at listening.

Focus, Focus and Focus!

Another challenge is maintaining focus. When you think about what you’re going to say next, you risk losing focus and missing important points said between the lines. Don’t misunderstand me—you will always lose focus to some degree. I believe that good entrepreneurs often have a “monkey mind,” able to juggle multiple thoughts simultaneously. Still, you need to concentrate on the data being shared in the moment. Focusing on the next question always detracts from what is most important right now. One piece of advice I received was to write down the question I want to ask on paper and then forget about it. Later, when you have time, you’ll revisit the paper and often find that many of those questions are irrelevant as the customer’s story unfolds.

The Most Important Question

Our mission as entrepreneurs is to create something people want. As simple as it might seem, this is a challenging idea.

First, we have many biases—we naturally tend to favor what we want rather than what customers truly desire. Moreover, what people want is often not clearly articulated; sometimes, even they aren’t sure what they want. I believe that guiding a customer to understand what they truly desire—and then having them reveal that information—is a skill that takes a lot of practice.

I’ve discovered that there are several questions which, when asked in the correct order, can lead customers to reveal valuable insights. The main problems we aim to solve—and the reasons users end up loving our products—are typically gaps in existing offerings. These gaps make customers struggle with what’s available and yearn for a solution that fills that void. Therefore, I’ve found that asking a simple question about an existing product—“What doesn’t work in _____?” (where _____ is the product or service you’re trying to improve)—is a golden question. If you listen carefully, you’ll be amazed to hear not only your hypothesis discussed but also the customer’s perspective, complete with practical examples. When the customer starts to elaborate and finishes their thought, one piece of advice I was given is to count to 10 in your mind before asking the next question. Often, the most interesting information emerges after that pause, when their brain takes a moment to process and analyze.

Document the Interviews and Read Them Again

I always document the interviews I conduct. Sometimes I use modern note-taking apps, and sometimes I write them down manually—I still haven’t decided which is better. While note-taking apps record the entire conversation with no information loss, I’ve noticed that some customers feel it’s rude to be recorded, and others don’t share all the details because they find it hard to reveal their true feelings, struggles with current products, or internal information when they’re being recorded. However, it’s always good advice to document the interview, review it, and compare it to others. You’ll invariably discover information you missed or didn’t have time to process during the conversation—information that is pure gold.

%20(1).png)

.png)